Policy Guide

Procurement Planning

Supplier Discovery

Supplier Management

Go To Market

Compliance Management

Evaluation & Award

Contract Management

Reporting & Analytics

See an overview of all the procurement modules.

Customer Experience

Flexible Ecosystem

World Class Security

See why customers choose the VendorPanel Platform.

Solutions

Bert Myburgh | 14 Feb 2022 | 10 min read

Ethical Procurement Explained: A Master Class in Best Practice

What is ethical procurement, why is it important and how can you adopt it within your business processes? We answer all of your questions.

What is Ethical Procurement?

Ethical procurement is behaviour which meets the standards of the procuring organisation and the expectations of society. Organisational standards include things like ethical behavior and social, legal and environmental obligations. In terms of social standards, most people expect an organisation to act as a good “corporate citizen” - and will voice their disapproval if it doesn’t!

To practice ethical procurement, having an ethical standards policy and a supplier code of conduct is a great start. However, there are a number of places this can fall flat.

To explore this point, let’s look at a simple example:

George issued Requests for Proposal (RFPs) with 90 per cent of the information needed to submit a winning bid. However, he had a relationship with one bidder who made secret payments to George in exchange for the “missing” information.

As a result, the bidder’s offer always scored most points in tender evaluation, so the recommendations to award to that bidder appeared sound and impartial. Sure, George’s RFPs did attract a few more questions from bidders than the RFPs issued directly by the procurement team. But hindsight is 20/20, right?

It doesn’t take a genius to know what George is doing is unethical. He’s securing personal gain from his professional role, and also not treating the bidders fairly or impartially.

What could have stopped George, if anything? Let’s talk about some of the control mechanisms that can be used to avoid this sort of unethical practice.

Common Control Methods to Promote Ethical Procurement

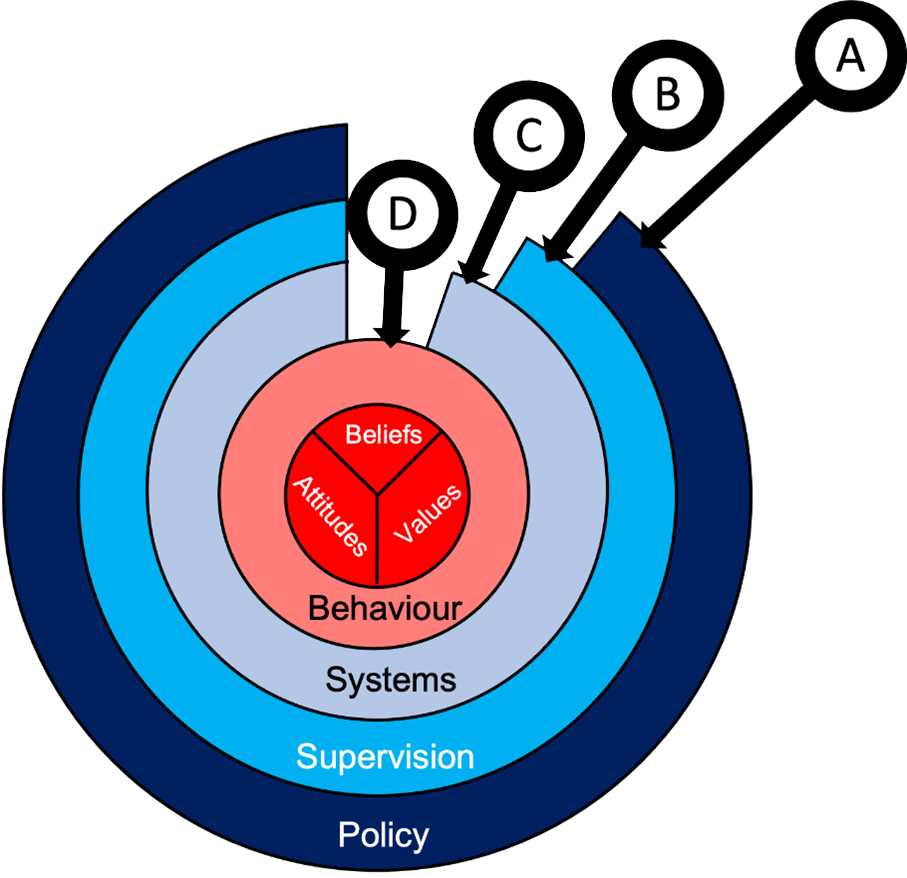

If you break it down, there are three layers of control that can protect an organisation from unethical conduct. These are policy, supervision and systems.

In our example, George certainly would have been in breach of any ethical procurement policy, and was presumably also under some form of supervision. However, neither of these factors would have prevented this unethical procurement practice. There may have been a few more questions for George’s RFPs, but which manager has the time to track this?

The third layer of control would be procurement systems. These provide transparency by documenting every step in the process and hardwiring good governance, such as the separation of roles.

Through the use of automation and “compliance by default” thinking, systems provide a stronger defense than just relying on policy or constant supervision. By having multiple controls, so long as one works, the organisation has a higher chance of avoiding unethical practice.

Why Personal Standards are Vital for Ethical Procurement

Even with these levels of control in place , they need to be supplemented by personal standards. Ultimately, humans are very clever, and may be able to find a way around any organisational control you put in place.

What happens then? In that case, ethical behavior is going to depend on the person’s personal value system.

One model of what drives our personal value system focuses upon the interaction of:

- Beliefs: A belief is an idea that we hold to be true.

- Values: What is important to you, like honesty, integrity and professionalism.

- Attitudes: How you approach other people and situations.

Research suggests that we develop beliefs from experience, from our education and from our culture. These beliefs then drive our values, which then frame our attitudes, which generate our behaviour.

In George’s case, his personal value system may have had the following elements:

- Beliefs: “I’m underpaid for what I do!”

- Values: “I need to support and be loyal to my family”

- Attitudes: “I’m smart enough to not get caught!”

The key point is that George’s behaviour is a consequence of the interplay of beliefs, values and attitudes. Compliance training may affect George’s behaviour in the short term, but if his personal value system is unaffected, the adherence to the rules may be shortlived.

The diagram above represents the combination of organisational (blue) and personal (red) factors when considering ethical choices.

We can use this framework to explore how different types of ethical misconduct may be detected by different controls, demonstrated below.

A bidder misses the closing date for a bid, and asks the client “Can I submit a late offer by email?” The client checks the policy which states that late offers can only be accepted if the tendering system was not available. As this was not the case, the client conforms with the governance and declines to accept a late offer.

In this example, policy acted as an effective control.

A current supplier has been red-flagged by a third-party information broker as being subject to investigation for the use of child labour in another country. The client asks their boss, “Can we still deal with a supplier who is red-flagged for human rights issues?” This is an example of how some ethical issues are not black-and-white or capable of definitive guidance in a policy document.

The supervisor may wish to consider the corporate structure of the supplier, the accuracy of the reporting about the alleged use of child labour and the timescale for any investigation into unethical practices. It is also likely that the organisation will consider the reputational impact on stakeholders in their own country when reaching a decision.

In this example, supervision acted as an effective control.

A staff member has created a phantom supplier, which they control, on the payment system. They have raised invoices from the supplier for a series of small sums which they themselves have approved for payment. Eventually, the value of sums paid to the phantom supplier increases to the point that the spend is detected in routine spend analysis and the fraud is uncovered.

In this example, the system acted as an effective control.

The point about these examples is that there is a wide range of ethical issues that can arise. Ethical misconduct can involve a lone operator within your organisation, suppliers acting corruptly with staff, suppliers acting corruptly with each other and even suppliers up the supply chain doing the wrong thing.

Having multiple layers of controls makes prevention and detection of unethical behaviour more likely.

The Impact of Poor Procurement Ethics

There may have been a time when a bribery scandal could be hushed up. Not any more, or at least not in most developed economies. The emergence of Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance (ESG) as a way of assessing the sustainability of investments has created an unprecedented level of visibility of the outcomes of firms’ business practices.

Pension funds and shareholder groups use ESG assessments as a way of insulating investments from the risk of loss of value due to bad press about corruption or human rights violations. This is based upon the belief that financial performance depends as much on a company’s social responsibility as on prudent financial management or operational results.

It means that unethical practices in procurement may hit the share price, affect senior management and even the Board. No wonder private sector firms take ethics seriously.

In the public sector, the “front page of the newspaper” test has always been applied to decision-making. But the digitisation of systems has created a new level of supply chain visibility. Hardly a month goes by without news articles about poor procurement practice somewhere.

The panic to procure PPE in 2020 led the UK government to award contracts for PPE without competition to a private equity firm, a pest control firm and a confectionery wholesaler. The majority of the products supplied by the firms could not be used. The allegations and ongoing investigations occupied the front page of newspapers for months causing reputational harm to the government, embarrassing senior ministers, and undermining public trust in the responsible management of public funds.

Who Judges If A Procurement Decision is Ethical or Unethical?

Individual members of staff make the first judgement, which may then be escalated for validation by senior managers. For high profile decisions, this may also be subject to the court of public opinion, including customers and society in general. Here is an example:

A news story reported that a driver employed to drive school buses in an adjacent county had a prior conviction for serious assault. This triggered all public authorities to ask their contractors to report on any drivers who had a conviction for a serious crime within the last ten years.

One company reported that an applicant driver had voluntarily disclosed that as a young man he was convicted of manslaughter. That was 12 years ago, and the conviction was now spent but he wanted to be honest and transparent.

What would you do? The driver has been honest and didn’t have to disclose his prior conviction. The decision depends upon the organisation’s risk appetite and their understanding of their societal obligations.

In this case, a senior manager decided that the driver could not be employed to drive school buses. They based their decision on the following personal value system:

- Beliefs: Human beings are capable of redemption (but some people do bad things).

- Values: My primary responsibility is to the school children and their parents.

- Attitudes: Even a small risk of re-offending is too great a risk.

The advice for anyone working in the procurement process is that if you are in doubt about an ethical choice, always escalate it to your manager. This applies especially if there is perceived, a potential or actual conflict of interest.

The Chain of Ethical Responsibility

A social enterprise won a contract with an extremely competitive bid. The supplier had been asked to check their figures, as the pricing was 10 per cent lower than any other bidder. They confirmed the arithmetic added up. The contract was small to the client but big for the social enterprise.

Their win was showcased in marketing communications by the client and the social enterprise alike. Newspaper articles celebrated the socially-responsible initiative. A couple of weeks later the CEO of the social enterprise revealed the truth; their costings were wrong and they would go out of business in a month unless they could raise their rates by at least 15 per cent.

What would you do? This example highlights that there is more to ethical practices than avoiding bribery or having a Modern Slavery Policy. There is no ‘right and wrong’ in this example, just a ‘least-worst’ outcome. This highlights that the way to manage ethical choices in procurement activities is to ensure that:

- The layers of organisational controls (policy, supervision and systems) are in place and any gaps in coverage are minimised;

- The people making choices have personal value systems that are broadly aligned to common organisational standards and community expectations.

The reason why personal value systems matter is that if all our organisational controls fail, the last line of defence is the behaviour of employees working in the procurement process.

In the short term, requiring staff to attend a training session on the procurement ethics policy may achieve compliance. A better option is to socialise the beliefs, values and attitudes that are consistent with the organisation’s culture. This may align choices along the chain of decision-making so that staff working in the procurement process make similar responsible choices.

Five Recommendations to Promote Ethical Procurement in Your Organisation

Ethical behaviour is about the choices that staff make every day. There is no point having a 75-page ethics manual if no-one reads it or understands it!

Let’s explore five steps that can help staff members to make the right choices, more often.

1. Review the Guidelines Issued to Staff About Ethical Procurement

Ask yourself the following questions:

- Are they accessible and written in simple language that makes sense to the reader?

- Does the scope of the content cover corruption, social and environmental ethical challenges?

- Are there examples and dilemmas to promote engagement?

2. Review the Guidelines Issued to Suppliers (E.g. Code of Conduct)

Ask yourself the following questions:

- Are they accessible and written in simple language that makes sense to the reader?

- Does the scope of the company's code cover suppliers' obligations in terms of corruption, Modern Slavery, social responsibility, workplace health and safety and environmental ethical challenges?

- Are there channels for suppliers to report potential issues?

3. Make Sure Supervisors Know What To Look Out For

Ensure supervisors and other professionals working around the procurement process are alert to the ‘red flags’ of unethical behaviour, such as:

- Unwarranted use of urgency provisions to sidestep scrutiny

- Unexplained wealth or conspicuous consumption

- ‘Presenteeism’ or a reluctance to take leave

- ‘Closed-loop’ decision-making systems

- The selection of direct negotiation as opposed to competitive tension as a strategic sourcing mechanism

- Some suppliers having win rates that are a lot higher than their peers

- Staff demonstrating a high level of risk tolerance and reluctance to discuss their decision making

4. Conduct “Hot Spot” Audits

Perform an audit of how existing systems would detect and prevent the most likely corrupt, social or environmental malpractice with first-tier suppliers or elsewhere in the supply chain.

5. Hold Discussions Around Ethical Behaviours

Conduct facilitated discussions with procurement teams about;

- Behaviours around ethical standards in contract negotiation that are (and are not) acceptable

- Attitudes that underpin these behaviours and reflect corporate standards of business ethics

- Values that underpin these attitudes and reflect corporate standards of business ethics

- Beliefs that underpin these values and reflect corporate standards of business ethics

Where to Begin?

Systems are a core part of any organisation’s controls. VendorPanel solutions help staff identify which procurement policies apply to any given purchase. Better still, they ensure staff go to market in a way that is compliant with organisational policies.

The platform does this by guiding staff through easy-to-follow steps, whether they are going to market for three quotes, or kicking off a formal procurement planning and approval process.

If you want to see what we can do, book a demo or contact us directly.

Sign up to our newsletter

Get insights, news, events and more direct to your inbox.

Further reading

Ready to Know More?

Get in touch, we'd love to hear from you.